The past two decades have seen unprecedented scrutiny of the work of colonial-era European scholars of Maghribi music, a reexamination that has helped to uncover the ideological and pragmatic contexts underlying much of North Africanist and Arabist musicology in the second half of the nineteenth century and the first half of the twentieth (Barbacane, 2012; Matsushita, 2021; Pasler, 2006, 2012-2013, 2016). In looking to Rodolphe d’Erlanger (Ben Abderrezak, 2018; Davis, 2004; Ghrab, 2018), Patrocinio García Barriuso (Calderwood, 2018), Alexis Chottin (Pasler, 2006), Henry George Farmer (Katz, 2015), and Jules Rouanet (Glasser, 2016; Khellal, 2018; Miliani, 2018) not only as sources of information about the Maghrib but as objects of study in their own right, many of the authors of this recent body of scholarship have drawn music into the critique of Orientalism that was initiated by Edward Said some forty years ago, and which arguably continues today in decolonizing guise.

If the self-reflexive contextualization and critique of colonial-era scholarship is necessary and productive, it also carries some dangers. Looking back on my own earlier research about musical revivalist discourse and practice in early twentieth-century Algeria, I recall the initial temptation, circa 2004, to treat European discourse about the Maghrib as hermetic, self-reinforcing, and, above all, powerful. This temptation was overdetermined in all sorts of ways. There was the cache of the Foucauldian paradigm. There was the archive itself, whose vast bulk was written by colonial officials, making access to indigenous voices a seemingly lost cause (it was of course convenient that this archive was in a language that at the time was more accessible to me than was Arabic!). It was far easier to treat the colonial discourse as a sealed-off whole, with the few indigenous voices that could be accessed fitting neatly into either “collaboration” or “resistance.”

One way around this problem is to counterbalance the weight of the archive with heightened sensitivity to the Maghribi musicians and scholars on whom colonial-era European scholars relied, sometimes with little or no acknowledgment. The strategy of working against the archival grain adopted in some recent works (see, for example, Ben Abderrezak, 2018, pp. 123-124; Calderwood, 2018; Glasser, 2016) has much to recommend it, but it too has its share of potentially awkward aspects. It can present Maghribi figures simply as adjuncts to a primarily European scholarly impulse. At worst, one can imagine such an approach framing the former as dupes of the latter, thereby pushing us once again into a totalizing antinomian trope. And this approach tends to continue to rely on official archives, threatening to distract us from the more subtle projects that existed alongside, were entangled with, or even preceded the more high-profile European publications.

How might we work around these traps, which risk reproducing a colonial logic under the guise of challenging it? One is to tune into Maghribi scholars’ work, both inside and outside direct colonial situations. For example, Carl Davila’s work has reconstructed the vigorous manuscript culture of Fes in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries (2013; 2016). Coming closer to the Moroccan encounter with modern European colonialism, Ibrahīm al-Tādilī’s work, written in the 1880s in Rabat, Morocco, has finally begun to receive scholarly attention (Benabdeljalil, 2011; Kara and Göpkinar, 2013). And there remain various figures inside clearly colonial situations who merit closer attention than they have so far received.[2] We can also start thinking more transnationally, both about European and Maghribi musicians and scholars: there are connections, sometimes quite subtle, across the Maghrib, both in the sense of local and translocal forms of discourse, inspirations, and rivalries, and there are connections further afield, pointing toward Western Europe but also to Egypt, the Levant, and Istanbul.

These pages try to sketch what a layered, spatially varied approach to contextualization can look like by exploring a single text, Kitāb kashf al-qinā‘ ‘an ālāt al-samā‘ (The Book of Lifting the Veil from the Instruments of Listening, henceforth Kashf al-qinā‘), written by Ghaouti (Ghaoutsi) Bouali (Abū ‘Alī al-Ghawthī), a teacher and prominent scholar of Arabic grammar and literature from Tlemcen. Although Kashf al-qinā‘ has been counted as the “first Algerian essay of a musicological character” (Guettat, 2004, p. 67), and its publication in 1904 coincided with several landmark works on the Algerian and Egyptian scenes, it has received minimal scholarly attention, and what little it has received tends to treat it as an oddity. Guettat has described Bouali’s notation as “rudimentary and unusable” (p. 67) and has pointed out his idiosyncratic technical vocabulary (p. 68). In Bouali’s own day, the book received a patronizing summary and review in the Revue Africaine by Mohammed Ben Cheneb, as part of his survey of Arabic publications of 1904-1905 (1906). On the other hand, Rouanet’s treatment of it in 1922 is superficially positive: Kashf al-qinā‘ is the only work by a Maghribi writer included in the sparse bibliography of eight “modern Arab authors” (pp. 2681-2682) in his La musique arabe essay, and in La musique arabe dans le Maghreb, Bouali is presented as the sole modern theorist in the Maghrib. However, unlike some of the modern theorists from the Mashriq with whom Rouanet engages at some length, such as Mikha’īl Mashāqa and Kāmil al-Khula‘ī, Rouanet is dismissive of Bouali’s work, effectively shunting the Maghrib to the margins of Arab musical theory while placing Maghribi music (and to a lesser degree, Arabic music more widely) under the monopoly of himself and his European colleagues:

Dans tout le Maghreb la partie théorique de la Musique arabe a échappé aux praticiens ; tous ceux que nous avons connus ignoraient même les petits traités publiés en Egypte par les modernes. Un seul essai a été tenté par le petit livre d'Abou Ali El Ghaouati [sic] (Alger, 1320). Kitab kashf al-qinā‘ ‘an ālāt al-samā‘ [sic] ; mais nous n'y trouvons, comme chez tous tes chanteurs et instrumentistes maghrébins, que des notions vagues, le plus souvent altérées et employant des termes dont la signification n'a plus de rapport avec la théorie qui existe encore en d'autres pays musulmans. (p. 2920)

In the following pages, rather than treating Bouali’s work as a marginal curiosity, or sequestering it on one side of a sharp civilizational divide,

I attempt to engage with Kashf al-qinā‘ as a cosmopolitan work that emerges from three overlapping contexts: one that is primarily French colonial (Tlemcen-Algiers-Paris), one that is primarily Arab (Tlemcen-Algiers-Cairo-Beirut), and one that is more specifically Maghribi (Tlemcen-Algiers-Tlemcen). By situating Kashf al-qinā‘ in these contexts, and by specifically linking these contextualizations to the structure of the text itself, I hope to show Bouali’s book to be simultaneously less anomalous and more remarkable than it might appear at first glance. In the process, I aim to demonstrate the possibilities and challenges of the broader investigative roadmap sketched above.

The structure of Kashf al-qinā ‘

Before placing Kashf al-qinā‘ in its three contexts, it is necessary to briefly sketch its structure. The purpose of this is both to orient the reader to the text—to think about the shape and internal composition of the text as object, so to speak—and to provide a conceptual vocabulary for linking the text to its contexts.

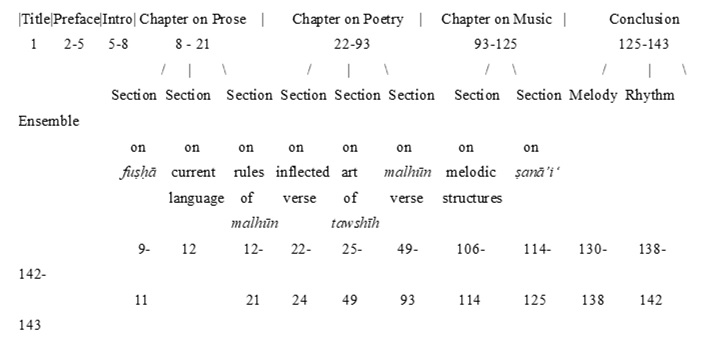

Printed autographically in Algiers in 1904 in the author’s own hand in a run of just 250 copies, Kashf al-qinā‘ presents itself as a study of music (2-3). Structurally, however, it is largely about poetry: after a short preface and introduction, the text consists of a sixteen-page chapter about prose and spoken Arabic, followed by a long chapter on poetry that is divided into a three-page discussion of classical metrical poetry, a 24-page section chiefly comprised of a collection of muwashshaāt, and a 49-page section that is largely a collection of colloquial poetry. It is only in the last third of the book that the author turns toward music per se, with a 33-page chapter about pitch and its representation, the form of musical instruments, rhythm and its representation, the melodies used for several pieces in the nūbat sīka and nūbat ghrīb (notated using a system of the author’s devising), and contemporary performance practice in Algiers and Tlemcen. This chapter on music apparently concludes the work, with the author dating it Thursday, Jumada II 3, 1321, corresponding to August 17, 1903. However, it is followed by an eighteen-page conclusion, dated nearly a year later, in which the author translates a long section drawn from the opening of the 1879 edition of Francisco Salvador Daniel’s 1863 La musique arabe and introduces the fundamentals of standard European staff notation. A rough sketch of the overall structure of the treatise, taking into account the author’s own division of the text into chapters and sections, is as follows, with the page numbers marked beneath:

This representation is helpful for seeing the thematic layout of the book.

It is also helpful for distinguishing various nested components of the text. We can conceptualize the title page, the preface, the introduction, and the conclusion as the outer frame of the text as a whole. In turn, we can conceptualize each chapter as being framed with its own unnamed introduction and conclusion and its various named subsections. Finally, the text can be conceptualized temporally in terms of a process punctuated by various moments: the moment before its writing, in which the author-to-be inculcates various other texts and genre frames upon which he will be drawing in the creation of his text, the moment of the writing of the work itself, and the moment of its publication (beyond what I have already mentioned, I will be largely leaving aside what Hanks has called the “after-text,” 1989, p. 96). As we start to place Kashf al-qinā‘ within its various contexts, it will be important to keep in mind its internal structure as well as these moments in the textual production process.

Tlemcen-Algiers-Paris

Not surprisingly for a book printed in Algeria in 1904, the ties of Kashf al-qinā‘ to its high colonial context are hard to miss. The internal evidence for this is concentrated in the work’s framing material, particularly on the title page and its preface: printed at the Imprimerie Jourdan, an Algiers-based press that specialized in government publications, the book begins with a dedication to Governor-General Charles Jonnart, “who has filled our country with justice and propagated landmarks and hospitals” (p. 5). Such a dedication is not unusual for Arabic-language publications of this period. Nor should this be seen as entirely an exercise in flattery, in that Jonnart was widely seen as a fair-minded reformer sympathetic to urban Muslim elites.

If we move beyond the words of the text itself to instead consider the correspondence surrounding its publication found in the archive, we quickly find that the coloniality of the text runs quite deep. Although it is not mentioned directly in the text itself, Kashf al-qinā‘ was printed through the support of the Service des affaires indigènes, recently established within the Gouvernement Général d’Algérie. By weaving between the text and what remains of the correspondence between Bouali and the officials from the Service des affaires indigènes, we can arrive at a fairly detailed reconstruction of the process of revision and negotiation that culminated in the book’s publication.

At the time of the book’s writing and printing, Bouali was a teacher of Arabic in the mosque of Sidi Bel Abbès. He completed the main body of Kashf al-qinā‘ in his home city of Tlemcen, ending just before the conclusion, in August 1903, after which he transmitted the text, with a dedication to Governor-General Jonnart, to the Service des affaires indigènes in Algiers for consideration for publication. It was then passed along for perusal to Abdelhalim Ben Smaïa from the Algiers médersa, who recommended that it be published. Dominique Luciani, the head of the Service (1901-1919; Pouillon 2008: 616), expressed to the Secretary General of the General Government his support for printing the work, citing his desire “to get the natives out of the routine of their old religious instruction.”[3] However, there was a refusal to do typeset printing on the basis of cost, and in April 1904 discussion was continuing as to whether printing would even be possible.[4] Autographic printing appears to have been the solution.[5]

Around this time is when officials from the Service des affaires indigènes began to request certain revisions to the manuscript. On June 7, 1904, Bouali sent the following short letter to Muhammad al-hafnāwī, who seemed to be the point of contact between Luciani and Bouali:

Praised be God the One

Our learned shaykh Sayyid Muhammad al-hafnāwī, upon you perfect peace. Since the arrival of your second letter I began doing what you indicated to me. It is hoped from you that you will send me what you have now so that I might add what I must add and then return it to you, God willing, right away. Upon you peace, from [me], al-Ghawth Abu ‘Alī, 7 June 1904.[6]

We can surmise from the shape of the published version that what had been requested of Bouali was the addition of a new conclusion. This closing section is a translation in two senses. First, the author quotes at length from the first nine pages of Salvador Daniel’s La musique arabe, largely a direct translation, with some omissions, rearrangements, paraphrasing, and emendation; this section is Salvador Daniel’s recounting of his own initiation into the indigenous music of Algeria and his general argument about the link between the latter and the music of medieval Europe. Second, Bouali follows this with a section introducing European notational conventions with regard to melody and rhythm/meter, which he presents as a summary of certain unnamed French texts with which he is becoming acquainted (p. 143). Bouali ends with a page about compound forms and ensemble playing with a conductor (p. 143).

On June 20, 1904, Luciani prepared a letter in Arabic addressed to Bouali. The heavily annotated draft reads as follows:

We were very pleased by your attempt to give [crossed out: a new method in the known style] an example of [melodies] in European musical [crossed out: language] notation, which expands the usefulness of your one-of-a-kind work that gathers together that which was dispersed [crossed out: illegible] elsewhere. I have requested the return of the book to you so that you might make this addition to it, which the petitioners/scholars/students [al-tullāb] await impatiently. We have sent it to you and God appoint that you might not delay in gracing us with it [crossed out: fully crowned]. Goodbye.

From the director of the Bureau of Indigenous Affairs in the Governmental General, Mr. Luciani.

In the margin, the letter reads, “It is requested of you that you [leave] your first example in the original version of the book [ahl al-kitāb], keeping them together, and that this not be neglected--most important.”[7]

Luciani’s letter suggests that it was important to him to set up a contrast between Bouali’s initial homespun if ingenious attempt to notate the melodies, on the one hand, and the standard European conventions for doing so on the other. It also suggests that Bouali sent them a draft of the addition, and then made this addition to the copy that had been in the hands of the Service. Luciani’s request also helps to explain the fact that Bouali ends the text twice, once in August 1903 (p. 125), and again a year later on the potent date of July 14 (p. 143). However, at least part of the introduction appears to have been rewritten to include mention of this new conclusion (p. 4); it is likely that Bouali simply recopied the entire text, with the added conclusion and either a new or updated preface.

Four days later, Bouali sent the completed book to the sous-préfet of Tlemcen, to be passed along to Luciani.[8] Shortly after, Bouali left Algeria to work at the Ecole Franco-Arabe at the French Legation in Tangier, returning some six months later due to illness, apparently resuming his work in Sidi Bel Abbès in 1905.[9] Meanwhile, the book had been printed; however, Bouali did not receive copies until July 1906, in response to his plea in March for a few copies.[10] He received twenty out of the 250 total, with the other copies being distributed to the médersas, military officers attached to the Service des affaires indigènes, the préfectures, the Résidence Générale in Tunis, plus various individuals, including the Orientalists Ignác Goldziher, Edmond Doutté, and Gaétan Delphin.[11]

With its publication and distribution, the archival trace of the connection between Bouali and the Service naturally ends. On the basis of subsequent writings, however, we know that by 1908 Bouali was teaching at the Grand Mosque in Tlemcen (Bel, 1908, p. 439). And by 1914-1915, Bouali was teaching at the Médersa of Tlemcen (Bouali and Marçais, 1917, p. 1), where he would remain (now a professeur and not simply a mouderrès) for the rest of his career. From his position at the Médersa of Tlemcen, Bouali engaged in a variety of scholarly projects, including the translation of Ibn al-Ahmar’s Histoire des Benî Merîn (1917), which he co-authored with Georges Marçais. He was also a close associate of William Marçais and provided expert advice regarding local poets of Tlemcen to the linguist Georges Colin.[12]

While Bouali’s book received little attention, it is certainly possible that its publication helped Bouali advance in his career. But neither this possibility nor the heavy involvement of the colonial apparatus in the reshaping and publication of Kashf al-qinā‘ is to accuse Bouali of cozying up to the colonial apparatus. Like many other reformist intellectuals teaching in the médersa system, Bouali was centrally concerned with the transmission of Algerian Arab-Islamic culture, a symbolic repertoire that would become a central discursive pillar of the independence struggle that developed decades after his death in 1933. After the Second World War, he would be warmly remembered as an effective and compassionate teacher by his student Mohamed Kazi Tani, a militant in the Association des Oulémas Musulmans Algériens (Kazi Tani, 1952, pp. 38-41). And Bouali was quite literally a grandfather to the post-independence Andalusi musical revival in Tlemcen thanks to the central role played there by his son, Mohamed Bouali. The foregoing narration of the publication history of Bouali’s book simply serves to point out its close entanglement with the colonial apparatus, and the way in which that entanglement influenced aspects of the text itself.

Tlemcen-Algiers-Cairo-Beirut

This first contextualization is enriching but by no means sufficient. Note that it focuses largely on one moment in the process of textual production, that of publication. Note too that the revisions that arose from the negotiation of publication are confined to the conclusion. This entanglement with the colonial apparatus is of course important; indeed, we would likely not know of Kashf al-qinā‘ had it not reached print, and the relationship with the Service reshaped the text in important ways. However, it is necessary to reach beyond the fine detail of the colonial archive and the effects of colonial power on the text’s framing material and its realization in print if we are to tune in to some subtler connections embedded in the text, most of them beyond the conclusion added at Luciani’s behest. These connections involve a lateral, East-West matrix that links Algeria to Egypt, to Beirut, to the Mashriq more broadly, and likely to Istanbul as well. These connections also happen to show Bouali to have had more access to current Arabic print culture from the Mashriq than is typically acknowledged in the literature on turn-of-the-century French Algeria.

Kashf al-qinā‘ is peppered with references to Arabic-language works coming from a wide range of periods. Throughout, Bouali cites classical authors associated with diverse fields, including, in the preface and introduction, al-Ghazālī, al-Isfahānī, Ibn Khaldūn, al-Tabarī, al-Mas‘ūdī, and al-Wāqidī; in the section on prose, Abū Tammām and al-Harīrī; in the section on metered poetry, al-Khalīl and Ibn ‘Abd al-Rabbih; in the section on tawshīh, the authors of the seven canonical muwashahāt; and in the section on music, Ibn al-Nabīh, al-Haskafī, Ibn Khallikān, and Ibn Rashīq. While Bouali may conceivably have known the writings of these authors through manuscript versions, it is more likely that he knew them through printed versions coming from Cairo and Beirut in the second half of the nineteenth century, either through travels outside Algeria or through nodes of entry within Algeria (such as Ahmed Ben Mourad Turki’s bookstore on rue Randon in Algiers; Ben Cheneb, 1906, p. 262n1). Bouali also shows himself to be aware of recent developments in Egyptian and Ottoman Arab intellectual circles, as is evident in his introductory discussion of Egyptian innovations with regard to punctuation (p. 6) and his quotation from the contemporary Palestinian jurist and poet Yūsuf al-Nabhānī (p. 5).

On its face si, the long chapter on music is focused on the Maghribi and more specifically Algerian context. The x pages Bouali devotes to instruments is centered on those used in the Algerian nūba practice, and his discussion of modes, performance practice, individual musicians, and specific melodies all focus on the nūba tradition of Tlemcen and Algiers. At the same time, Bouali shows himself to have also been aware of musicological works coming from Egypt, which had become relatively numerous since the 1856 publication of Shihāb al-Dīn’s Safīnat al-mulk wa-nafīsat al-fulk (The Ship of State and the Vessel’s Gem). Bouali cites only one by name: ‘Uthmān ibn Muhammad al-Jundī’s 1895 treatise Risālat rawh al-masarrāt fī ‘ilm al-naghamāt (Treatise on the Garden of Delights in the Science of Songs) (96). However, he also mentions another one—likely Muhammad Darwīsh’s 1902 safā al-awqāt fī ‘ilm al-naghamāt (The Serenity of Seasons in the Science of Songs)—without giving its title:

I saw a book of a learned Egyptian in which the author testifies to the perfection of his culture by adopting in it the practice of naming the soft sound in the percussion the tak and the loud sound the tum, and he used a simple dot for the tak in this manner (.) while the symbol for tum is a small circle like this (o). And there is no shame if I follow in his tracks and I adhere to his usage. (p. 106; for the corresponding convention in Darwīsh, see 1902, p. 21)

Beyond Bouali’s direct quotation from al-Jundī concerning the Persian names for the steps in the scale (p. 96), there are several passages that suggest that Bouali found inspiration from his work. For example, Bouali seems to paraphrase al-Jundī in discussing the strings of the ‘ūd (compare al-Jundī p. 7 and Bouali p. 107), as well as in his discussion of the adab of the singer (al-Jundī p. 21 and Bouali p. 94). In turn, al-Jundī’s and Darwīsh’s works borrow liberally from the stream of printed musicological publications reaching back to Safīnat al-mulk (and very likely a stream of manuscript writings that preceded and ran alongside those printed works).

While an extensive comparison of Kashf al-qinā‘ with al-Khula‘ī’s Kitāb al-mūsīqā al-sharqī (The Book of Eastern Music) is not possible here, it makes sense to think of these two publications of 1904 together, despite their considerable difference in length and detail. Both works were emerging from a largely Egyptian musicological conversation of preceding decades that nevertheless drew extensively on medieval models (Popper, 2019). Both combine attention to music theory, poetry, adab, religious considerations about the morality of music, contemporary performance practice, and instruments with an eagerness to use notation to preserve music from what they view as the threat of loss. Of course, Bouali is attuned to Algerian and Maghribi specificities, but this is very much in keeping with the attention to Egyptian specificities evident in al-Khula‘ī and his predecessors. In this sense, Kashf al-qinā‘ can be read as an Algerianization of a nascent Arab musicological model arising primarily from Egypt.

So far, I have been pointing out connections to Egypt that show up in various ways in the main body of Bouali’s text. However, such connections might be found as well in his concluding section that focuses on European staff notation. While Bouali states that he is drawing from French sources (p. 143), it is also possible that he drew from Arabic manuals printed in the Mashriq as well. His language in the preface suggests at least an awareness of Arabic-language “imitators” with regard to European staff notation:

And the conclusion is an illustration and interpretation of this art among its European practitioners and their imitators, extending its usage eastward and westward, universally. The Muslim disregarded it, and [this conclusion] spreads this universal convention once again, so that the book may be, with God’s help, unique in its kind. (p. 4)

Broaching the possibility that Bouali was drawing from the Mashriq does not mean that he was somehow bypassing France in these sections. French enjoyed great prestige in Egypt, and some of the Mashriqi printed works dealing with music drew on French models and vocabulary. This is evident in Ghārdūn’s 1855 treatise (Poché, 1994, p. 62n4), as well as in Amīn al-Dīk’s 1902 Nayl al-arab fī mūsīqā al-afranj wa-l-‘arab (The Attainment of Skill in the Music of the Europeans and Arabs) and al-Khula‘ī’s 1904 Kitāb al-mūsīqā al-sharqī. Ironically, the prestige of the French language in the Mashriq was also a way in which Arabs in the Mashriq came to be aware of Algerian music, as in the case of Philippe El Khazen’s preface to his printed collection of muwashahāt from an early modern Algerian manuscript, where the author cites a correspondent’s description of music-making in Algiers in the Paris-based daily Le Temps (El Khazen, 1902, p. vi). In other words, the crucible of French Algeria existed within a wider, more diffuse regional situation in which French was serving as an intellectual lingua franca for a wide range of Arabic speakers. This may still be an imperial France, but its language may have been entering into Bouali’s text via Cairo and Beirut as well as via colonial Algiers. Despite this other possible itinerary, for now it is a safer assumption that Bouali’s direct guides with regard to European staff notation were coming from France rather than from the Mashriq.

Tlemcen-Algiers-Tlemcen

Moving into the East-West Arab context has permitted a somewhat closer engagement with an aspect of Kashf al-qinā‘ that goes beyond its framing material and the moment of publication. In turn, turning toward the third and final context—that of the Maghrib itself, and of Tlemcen more particularly, both colonial and precolonial—allows us to start to engage with the text as a whole, and not only with its chapter on music.

Ironically enough, there are ways in which the Maghribi dimension of Kashf al-qinā‘ is the most difficult to trace. Given the fact that Bouali’s book was the first of its kind in Algeria, it is not so surprising that his citation of other printed books from the Maghrib is very slight: the one direct reference I found is to Al-anīs al-mutrib fīman laqiyahu mu’allifuhu min udaba’ al-maghrib (The Singing Companion to Those the Author Met of the Maghrib’s Men of Letters), an eighteenth-century collection of biographies of Moroccan poets, including samples of their oeuvres, that had been printed lithographically in Fes in 1898. This collection includes a section centered on Muhammad al-Bū‘aṣāmī (pp. 168-193), a key compiler of Moroccan nūba poetry and music theorist active in the first half of the eighteenth century. Part of this section is a discussion of the playing of the ‘ūd, but it does not appear to be a direct source for Bouali’s own discussion of the instrument. Another printed work by a Maghribi writer that Bouali cites is al-Nāsirī’s Kitāb al-istiqsā li-akhbār duwal al-maghrib al-aqsā (The Book of Investigation into the Annals of the Moroccan Dynasties), a groundbreaking history of Morocco that had been printed in Cairo in 1894/1895. A conspicuous absence is the Ibrahīm al-Tādilī’s recently penned musicological tour-de-force, Aghani al-siqa wa-maghani al-musiqa, awal-irtiqa ila ulum al-musiqa (The Songs of the Waterskin and the Abodes of Music, or the Ascent toward the Sciences of Music), which was circulating in multiple manuscript copies in Morocco at the time.

But these silences and tenuous links to the modern Maghribi literary field should not distract us from the firm rooting of Bouali’s work in the Maghribi social and artistic world. I have already mentioned that we can read the musicological aspects of the book as an Algerianization of a modern Arab musicological tradition centered on Egypt. This does not do justice to the work as a whole, however, which is weighted more toward poetry than to music, despite its ostensible focus on the latter (pp. 2-3). In turn, taking seriously the priority of poetry in this work allows us to begin to understand Bouali’s logic, which is oriented firmly toward the Maghrib while seamlessly connecting his cultural world to the Mashriqi past.

The key theme of Kashf al-qinā‘ that facilitates the vast geographic and thematic reach of the slim volume, and that helps to account for the intense focus on language in a book ostensibly focused on music, is the defense against loss over time and space. Bouali posits that the science of Arabic grammar arose from the danger the Arabic language faced from its rapid dispersal through the expansion of the Arab-Islamic empire (p. 11). Verse is likewise presented as a protection against the dispersal that everyday prose faces (p. 92), and Bouali likewise frames al-Khalīl’s meters as an attempt to protect against the loss of the ancient Arabic poetic tradition (p. 23). For him, the dangers that the grammatical and metrical tradition worked against were tied up with the rise of various Arabic vernaculars. While Bouali laments the problems posed by the diglossic situation in Arabic (p. 11) and paints the grammarians and al-Khalīl in heroic colors, he also treats the Arabic vernaculars as a fact of life worthy of scholarly inquiry. Even if he is often eager to point out the derivation of colloquial speech from classical sources, Bouali devotes sustained attention to Arabic dialectology, with attention to Egyptian, Hijazi, and, most of all, Algerian and Moroccan pronunciation and lexicon (pp. 12-21).

His comparative impulse allows Bouali to differentiate broadly between Maghribi and Mashriqi taste and aesthetics. It also allows him to move from classical Arabic verse in Khalilian meters to the Andalusian strophic tradition, and from there to its transformation into the colloquial poetic tradition specific to western Algeria and eastern Morocco, with its own metrical exigencies tied to the particularities of Maghribi spoken Arabic. This is what then allows Bouali to turn his attention to specific poetic texts from the hawzī tradition of Tlemcen, with some attention to the musical performance practice surrounding these poems in western Algeria (p. 93) and Morocco (pp. 88-89).

When Bouali finally pivots to direct discussion of music, his focus is on the nūba practice that highlights mainly the muwashahāt, not the malhūn poetry. But the logic of the turn to music in the last section follows the logic of the rest of the book, in that here again he is spurred on by the danger of dispersal. In this case, it is not the dispersal of poetic texts themselves so much as the dispersal of the melodies to which they are sung. It is because of the lack of musical notation that the melodies of poetic texts have either been lost or are in danger of disappearing. The melodies here are understood emphatically as a dimension or adornment of the poems, so that singing and instrumental music are treated primarily as a vehicle for poetry. For example, in describing the tūshiya, Bouali writes that it is “a movement with instruments alone, without intoning [takallum] a metered poem or zajal over it,” whereas an msaddar is“a slow movement in which the notes are held longer, over which he [the leader of the ensemble] and those with him intone [yatakallim] a metered poem” (p. 123).[13] But just as poetry has staying power that prose lacks (p. 92), Bouali treats sung poems that lack notation as melodically ephemeral (p. 108). This is what leads him to offer his notational system, which he then uses to transcribe pieces from two nūbāt (pp. 113-122).

The impulse against dispersion of melodies is in turn tied to the impulse against the loss of other kinds of musical knowledge, particularly with regard to modes. Bouali is intrigued by the story of the loss of modes and nūbāt, and he also shows a philological fascination with comparative knowledge.

A localized, intra-Maghribi comparative impulse is particularly acute in the discussion of dialectology and, most of all, music. With respect to the latter, Bouali’s residence for a time in Algiers, and his contact with students and scholars from other parts of Algeria (and possibly from Tunisia as well), is generative, both with regard to understanding how the nūba tradition differs between Tlemcen, Algiers, and Constantine (p. 101n,

pp. 122-124) and with regard to how the tradition experienced decline:

I have found reports that indicate that in the lands of al-Andalus this art contained 24 modes/suites, while in our age what remains of these are only twelve modes in the mouths of the singers. There was in Tlemcen a Jew named Maqshīsh who I used to spend evenings listening to, and he had command of sixteen modes, and today we have those who are deemed praiseworthy and skilled for knowing but four.

While I am a Tlemcenian by residence and birth I lived in Algiers for two years in pursuit of noble learning at the upper college. With my peers there, who were from all the Algerian regions and from the vicinity of Tunis, we were bound to talk about what is now practiced in our regions, on the basis of eyewitness or by hearsay, and we would say, “Confirmation is with God.”

What is required in this art is the fixing of melodies and the placement of notes in conventionalized form. I have happened upon more than 1,003 qawā’id and azjāl where the record is content to convey only the words of the first hemistich, and that it is sung according to the dhīl or māya mode, for example, but all one understands by the word dhīl or māya is that the final note will be dhīl or māya, leaving us without an understanding of when the singer should ascend, descend, stay in the middle, and so on. If we had a system of conventionalized symbols for making all this precise, then a hundred choice melodies from the age of dynasty of Fes would have been conserved, and the people of al-Andalus would have taught us how their tawāshīh were sung. This convention would be for the preservation of melodies in the same way that writing preserves words and pronunciations. (pp. 108-109)

Bouali was by no means the only indigenous Algerian writing about music in this moment, nor the only invoking the danger of loss as a spur for his work. Edmond Nathan Yafil’s famous compendium of nūba texts appeared in the same year, as did nūba texts published by Mahmoud Ould Sidi Said in cooperation with the Arabist Joseph Desparmet (Desparmet 1904). Closer to home for Bouali, the Tlemceni musician, schoolteacher, and scholar Mostefa Aboura was in this very moment engaging in an ambitious project of musical transcription of the nūba repertoire and its adjuncts, mainly as he encountered it in Tlemcen but with some comparative attention to Algiers, where he too had studied. It is difficult to imagine that Aboura and Bouali would not have known one another and have known of one another’s projects, and a comparative study of their work would considerably enrich our understanding of musical and intellectual life in Tlemcen and the wider country in this period. While Aboura never directly published his labors, some of them would see the light of day in Rouanet’s 1922 essay, where the author wrote in a footnote,

Les textes musicaux de Tlemcen ont été recueillis par M. Mostefa Aboura, instituteur, musicien très distingué non pas seulement en musique arabe, mais en musique européenne, excellent clarinettiste, qui nous a donné une collaboration intelligente et dévouée. (p. 2876)

On the one hand, the story of Rouanet and Aboura—a story that has yet to be told in full—points to entanglement between Algerian and French figures, between colonized and colonizer. I will return to this possibility in a moment. But for the time being, I want to underline the fact that there was a lively scene of indigenous Algerians engaging in musicological thought and writing, and who drew on textual practices associated with Europe while at the same time drawing on textual traditions that had long been indigenous to the Maghrib. Not unlike al-Tādilī a few decades earlier, they were all to varying degrees expressing an acutely comparative and, by extension, philological curiosity that was oriented primarily to the Algerian and Maghribi context while also drawing on broader Arab traditions of scholarship. The work of Ghaouti Bouali is the most fully elaborated example of this indigenous musicological thread at this turn-of-the-century moment.

Conclusion

The foregoing meditation on Bouali’s book has emphasized the importance of contextualizing it within various frames: a French Algerian frame that emphasizes coloniality, a Maghrib-Mashriq frame that emphasizes lateral connections to Egypt and the Levant, and a more specifically Maghribi frame that situates Bouali within an Algerian and Moroccan context that partly predates French intrusion. None of these contextualizations cancel out the others. Rather, they highlight three different dimensions and frames of reference in which Bouali was working.

At the same time, these dimensions are not equally weighted, and what we make of them depends on what kinds of sources and what parts of the text we attend to. If we focus on its framing material and the process of bringing it into print, the colonial dimension comes to the fore. But if we pay attention to the intertextual links, the East-West connections between Maghrib and Mashriq loom large, particularly when we focus on Bouali’s chapter devoted to music. And if we pay attention to the linguistic, poetic, and musical materials and personages with which Bouali is engaging throughout his text, the Maghribi and more specifically western Algerian dimension of the work is highlighted. Note that the paper trail and the interior of the text stand in inverse proportion: the deeper we move into Kashf al-qinā‘structurally speaking, the further adrift we become from the state archive and the printed word.

The foregoing exercise is, then, a plea to keep multiple contexts in mind, and with them multiple sources. One possible critique is that thinking in terms of three distinct (even if overlapping) contexts unfairly partitions actors and discourses from one another along lines of language, civilization, culture, and ethnicity. After all, can we really separate Aboura or Yafil from Rouanet, or Bouali from Luciani, or Mashāqa from the American missionaries in Beirut, or al-Khula‘ī from Thomas Edison? The answer, of course, is no. But at least temporarily thinking in terms of multiple contexts is helpful for constructing a narrative that is more complex than an overdetermined story of Westernization or colonial imposition. Furthermore, it allows us to start imagining more localized stories of modernism and modernization (Seggerman, 2021). If it is possible to think of Bouali in terms of an Algerian Arabophone domestication of European modernist discourses, in part translated via Egypt, it is also possible to think of him in terms of a Maghribi modernist discourse that emerges seamlessly from indigenous sources and forms, some of them of considerably antiquity.

It is also helpful to reverse the terms of some of the preceding questions. Is it possible to think about Rouanet without Yafil and Aboura, for example, or Chottin without Moulay Idriss? In these particular instances, we can again answer no, in that Rouanet and Chottin depended on the work of their Maghribi interlocutors to make their own work possible. But I would like to conclude by airing the possibility of answering in the negative from yet another angle. For example, what if we thought about European musicological interest in Arab music as following in the footsteps of Arab scholars who were their contemporaries? To move eastward and a little backward in time, what if we read al-‘Attar and Mashāqa as the starting point for J.P.N. Land and others, for example? What if we read Aboura and Yafil as the proximate starting point for Rouanet? In other words, instead of uncovering the Arab scholars and musicians working behind the scenes for d’Erlanger, Rouanet, and Chottin, what happens if we flip the script, and view the Europeans as rushing to catch up with the work of their Arab counterparts, and perhaps in some instances even absorbing and transforming indigenous narratives of loss? Of course, one could then counter that their Arab counterparts were in turn inspired by trends originating in Europe. But the point is that we probably cannot stop at some clear moment of origination. Equally, we cannot simply treat the field of discourse as an undifferentiated whole. In order to uncover a dialectic, we will need to recognize multiplicity. In such matters, Ghaouti Bouali remains an effective and compassionate teacher.

Bibliography

Archival Sources

Centre d’archives d’outre-mer, Gouvernement Général d’Algérie, 9H/37/18.

Centre des archives diplomatiques de Nantes, Archives des Postes, Tanger, Légation et Consulat, 517, Série A.

Bibliothèque nationale de France, Département des manuscrits, Papers of Georges Colin.

Printed Sources

Al-‘Alamī, A. (1898). Al-anīs al-mutrib fīman laqiyahu mu’allifuhu min udaba’ al-maghrib. Al-matba‘a al-fahsiyya.

Barbacane, K. (2012). On Colonial Textuality and Difference: Musical Encounters with French Colonialism in Nineteenth-Century Algeria.

[Doctoral thesis, Columbia University].

Bel, A. (1908). La population musulmane de Tlemcen. In A. van Gennep (Ed.), Revue des études ethnographiques et sociologiques (pp. 417-447). Libraire Paul Geuthner.

Ben Abderrazek, M.S. (2018). La contribution d’Antonin Laffage à la musicologie francophone du monde arabe. Revue des Traditions Musicales 12, 123-141.

Ben Cheneb, M. (1906). Revue des ouvrages arabes édités ou publiés par les musulmans en 1322 et 1323 de l’hégire (1904-1905). Revue Africaine 50 (250), 261-296.

Benabdeljalil [bin ‘Abd al-Jalil] , A. (2011). Aghani al-siqa wa-maghani al-musiqa, aw al-irtiqa ila ulum al-musiqa. Akadimiyyat al-mamlaka

al-maghribiyya.

Bouali [Abū ‘Alī], G. (1904). Kitāb kashf al-qinā‘ ‘an ālāt al-samā‘. Imprimerie Jourdan.

Bouali, G. & Marçais, G. (1917). Histoire des Benî Merîn, rois de Fâs, intitulée Rawhat en-nisrîn (Le Jardin des Eglantines). Maison Ernest Leroux.

Calderwood, Eric. (2018). Colonial al-Andalus: Spain and the Making of Modern Moroccan Culture. Harvard University Press.

Darwīsh, M. (1902). safā al-awqāt fī ‘ilm al-naghamāt. Matba‘at al-tawfīq.

Davila, C. (2013). The Andalusian Music of Morocco: Al-Āla: History, Society and Text. Reichert Verlag.

Davila, C. (2016). Nūbat Ramal al-Māya in Cultural Context: The Pen, the Voice, the Text. Brill.

Davis, R. F. (2004). Ma’lūf: Reflections on the Arab Andalusian Music of Tunisia. The Scarecrow Press, Inc.

Desparmet, J. (1904, February 27). Nubat al-Andalus. Le Tell: Journal politique et des interets coloniaux.

al-Dīk, A. (1902). Nayl al-arab fī mūsīqā al-afranj wa-l-‘arab. Al-matba‘a al-kubrā al-amīriyya.

Ghārdūn, T.B. (1855). Mukhtaṣar yataḍamman qawā‘id aṣliyya min ‘ilm al-mūsīqā. Matba‘at Būlāq.

Ghrab, A. (2018). Le baron Rodolphe-François d’Erlanger et les débuts de la musicologue francophone en Tunisie. Revue des Traditions Musicales 12, 151-161.

Glasser, J. (2016). The Lost Paradise: Andalusi Music in Urban North Africa. University of Chicago Press.

Guettat, M. (2004). Musiques du monde Arabo-Musulman : Guide bibliographique et discographique, Approche analytique et critique. Editions Dar al-'Uns.

Hanks, W.F. (1989). Text and Textuality. Annual Review of Anthropology 18, 95-127.

al-Jundī, ‘U. M. (1895). Risālat rawḍ al-masarrāt fī ‘ilm al-naghamāt.

Al-maṭba‘a al-‘umūmiyya.

El Khazen, P. (Ed.). (1902). Al-‘adhāra al-mayyisāt fī al-azjāl

wa-l-muwashshaḥāt. Maṭba‘at al-arz.

Kara, H. & Göpkinar, Y. (2013). Musik, Kultur und Gesellschaft in Marokko: Ibrāhīm at-Tādilī ar-Ribāṭī und seine Sicht auf die andalusische. Oriens 41(1/2): 159-183.

Katz, I. (2015). Henry George Farmer and the First International Congress of Arab Music (Cairo 1932). Brill.

Khellal, N. (2018). L’image de la musique kabyle dans les écrits musico-orientalistes de Francisco Salvador-Daniel et Jules Rouanet. Revue des Traditions Musicales 12, 109-121.

al-Khula‘ī, K. (1904). Kitāb al-mūsīqā al-sharqī. Matba‘at al-taqaddum.

Matsushita, E.A. (2021). Disharmony of empire: Race and the making of modern musicology in colonial North Africa. [Doctoral thesis, University of Illinois].

Miliani, H. (2018). Déplorations, polémiques et stratégies patrimoniales : á propos des musiques citadines en Algérie en régime colonial. Insaniyat 22(79), 31-47.

al-Nāṣirī, A.K. (1894/1895). Kitāb al-istiqṣā li-akhbār duwal al-maghrib al-aqṣā. Al-maṭba‘a al-bāhiya al-miṣriyya.

Pasler, J. (2006). Theorizing Race in Nineteenth-Century France: Music as Emblem of Identity. The Musical Quarterly 89(4), 459-504.

Pasler, J. (2012-2013). Musical Hybridity in Flux: Representing Race, Colonial Policy, and Modernity in French North Africa, 1860s-1930s. Afrika Zamani 20-21, 21-68.

Pasler, J. (2016). The Racial and Colonial Implications of Music Ethnographies in the French Empire, 1860s-1930s. In V. Kurkela & M. Mantere (Eds.), Critical Music Historiography: Probing Canons, Ideologies and Institutions (pp. 17-43). Routledge.

Poché, C. (1994). De l'homme parfait à l'expressivité musicale: Courants esthétiques arabes au XXe siècle. Cahiers de musiques traditionnelles 7, 59-74.

Popper, T. (2019). Musicological Writing from the Modern Arab “Renaissance” in Nineteenth and Early-Twentieth-Century Syria and Egypt. [Doctoral thesis, University of California Santa Barbara].

Pouillon, F. (Ed.). (2008). Dictionnaire des orientalistes de langue française. Editions Karthala.

Rouanet, J. (1922). La musique arabe. In A. Lavignac & L. de la Laurencie (Eds.), Encyclopédie de la musique et dictionnaire du Conservatoire

(pp. 2676-2812). Delagrave.

Rouanet, J. (1922a). La musique arabe dans le Maghreb. In A. Lavignac

& L. de la Laurencie (Eds.), Encyclopédie de la musique et dictionnaire du Conservatoire (pp. 2813-2939). Delagrave.

Said, E.W. (1979). Orientalism. Vintage Books.

Salvador Daniel, F. (1879). La musique arabe : ses rapports avec la musique grècque et le chant grégorien. Adolphe Jourdan.

Seggerman, A.D. (2021). Modernism on the Nile: Art in Egypt between the Islamic and the Contemporary. University of North Carolina Press.

Shihāb al-Dīn, M.I. (1856/1857). Safīnat al-mulk wa-nafīsat al-fulk. Cairo.

al-Tādilī, I. (2011[1884-1885]). Aghānī al-siqā wa-maghānī al-mūsīqā,

aw al-irtiqā ilā ʻulūm al-mūsīqā. Akādīmiyyat al-mamlaka al-maghribiyya.

Yafil, E.N. (1904). Diwān al-aghānī min kalām al-andalus. Yafil.

Yafil, E.N. (1904). Majmū‘ al-aghānī wa-l-alḥān min kalām al-andalus. Yafil.

Appendices

Jules Rouanet (1858-1944): An Ideological Biography

Jonathan GLASSER[14]

A close look at Rouanet’s career as a journalist, musicologist, and jack-of-all-trades intellectual illuminates a great deal about the colonial cultural politics of Third Republic Algeria and vice versa. Born in Saint Pons in Clermont-l’Hérault in 1858, Rouanet arrived in Algeria along with his wife, children, and parents in the 1880s.[15]From a middle-class milieu (his father was a dyer), Rouanet found in the colonial Algerian context fertile ground for social advancement by combining his background as an agricultural engineer with his skills as a journalist and cultural critic.[16] He also found in colonial Algeria a cause into which he threw himself with great energy, making him not only a commentator but also a booster and militant for settler interests. His early editorial and journalistic work at the Gazette du Colon and L’Akhbar, where he specialized in agricultural affairs, intersected with his role as secretary of the Comice agricole de Boufarick and his efforts to establish a musée commercial in Algiers.[17] After the death of one of his sons in 1890, Rouanet appears to have briefly tried his hand at journalism in Paris, before settling there for a time in 1892 as sous-directeur at the Musée Commercial de l’Algérie, a venture of the Government General.[18] By 1897, however, he was back in Algiers, continuing to write largely about agricultural matters and settler affairs. Despite a period beginning in 1899 as editor of the short-lived weekly Journal des Colons, Rouanet was now mainly associated with La Dépêche Algérienne, where he would take on an increasingly prominent role over the next four decades.

Much of Rouanet’s journalistic output was focused on agriculture and on economic affairs more broadly, sometimes under the name Mestré Ramon.[19] But from the beginning of his journalistic career, Rouanet also wrote frequently about art and music, sometimes signing his articles as Raoul d’Artenac.[20] As was the case in his agricultural boosterism, Rouanet’s musical interests were not confined to the newspaper columns. In 1898 Rouanet threw himself into musical activities on his return to Algiers through his founding of the Petit Athénée, a “Société Littéraire Artistique et Scientifique.”[21] Serving as a library and a pedagogical and performance space, the Petit Athénée was an important promoter of European classical music in the capital at the turn of the century. Indigenous Algerian music was decidedly absent from the Petit Athénée, as were indigenous Algerians themselves—no Muslims seem to have been members, and in keeping with the ubiquitous and virulent antisemitism of the moment, its regulations explicitly excluded Jews.[22] Rouanet’s association with the Petit Athénée did not last long—ill health and internal disputes spelled the end of his leadership by 1904, and a year later the association had disbanded, its space now renamed the Salle Barthe.[23] Nevertheless, Rouanet would continue to be closely connected to European classical music, both as a reviewer and as a teacher of piano, well into his old age.[24]

Rouanet’s experience in the Petit Athénée coincides with the beginning of his involvement in Arab music. His attention to indigenous artistic forms starting around 1904 did not come entirely out of the blue: in 1897 Rouanet had published “Pour les tapis algériens,” which called for the revival of Algerian textile art. His engagement with Arab music, however, would go much deeper and extend over several decades. It began at the behest of the Government General, which set him the task of studying “la musique arabe et la constitution d’un recueil des pieces originals et intéressantes qui subsistent en Algérie, en Tunisie, en Sicile, en Espagne et chez les divers peoples musulmans” right around the time when he was leaving the Petit Athénée.[25] The impulse to study Arab cultural production was very much in keeping with the zeitgeist surrounding the tenure of Governor-General Charles Jonnart, whose administration’s interest in documenting and promoting a Hispano-Mauresque aesthetic earned him the affection of many elite urban Algerian Muslims, even if Jonnart’s leadership ultimately proved ineffectual in improving the everyday life of most Algerian Muslims. This project brought Rouanet into direct and sustained contact with the young Algerian Jewish musician and scholar Edmond-Nathan Yafil, and through Yafil, Rouanet came to know a range of leading Algerian musicians, including Mohamed Ben ‘Ali Sfindja, the doyen of the nûba repertoire of Algiers. The following excerpt from a letter to the Governor General published in the columns of La Tafna in 1905, signed El Magharbi, gives a sense of how Rouanet’s work was being received in some circles:

Depuis quelques temps, il semble qu’un esprit nouveau - rien de celui de Spuller - règne en Algérie.

C’est un esprit fait d’apaisement, de bonne entente, de concorde entre les divers éléments composant la population algérienne…

Mais, chose encore particulièrement digne de remarque et comme un signe bienfaisant des temps : l’on dirait que le colon et l’indigène dont l’accord avait toujours paru utopique vivent aujourd’hui dans un esprit de mutuelle cordialité. Serait-ce à la suite de quelques concessions tacites réciproques ?

En vérité ce nouvel état de choses moral est dû à votre politique sage, bienveillante et tolérante. Grâce à des mesures administratives très habiles et très appropriées à la situation générale du pays, et, d’autre part, appliquant la doctrine de Lissagaray : soyons arabojustes, vous avez su ramener la confiance et faire renaître l’union dans tous les milieux : les colons ont trouvé en vous le défenseur éloquent et ardent de leurs multiples intérêts, tandis que les indigènes, eux, se plaisent à reconnaitre en vous l’administrateur juste et impartial en même temps que l’ami et le tuteur dévoué et bienveillant.…

Tout récemment encore, afin de donner aux indigènes une preuve de plus de vos sentiments aimables à leur égard vous avez résolu de vous faire hardiment le protecteur et le conservateur de leur musique qui tendait à disparaître : un homme de talent, d’une compétence indiscutable, M. Jules Rouanet fut chargé officiellement par vous de la mission difficultueuse entre toute de la diffusion et de la conservation de la musique arabe.

Outre que l’intention est éminemment louable, j’y vois encore pour ma part un but d’ordre plus élevé : en confiant à notre distingué confrère le soin de noter et d’écrire la musique arabe pour en faire jouer de temps à autre quelques morceaux par nos musiques régimentaires, vous avez sans doute pensé et avec raison qu’en groupant autour de celles-ci des auditeurs de différents cultes, ce serait un moyen de les rapprocher et de créer entre eux un certain courant de sympathie et de bonne harmonie (sans jeu de mots).

Mais il faut espérer que la mesure prise par vous pour la ville d’Alger sera étendue à toute l’Algérie et qu’il sera bientôt donné à toutes les grandes villes algériennes de pouvoir applaudir à chaque concert un ou deux airs arabes choisis dans le répertoire de M. Rouanet : les indigènes qui sont très impressionnables et très sensibles seront des premiers à vous en être reconnaissants.

Et puis n’oublions pas que la musique qui adoucit les mœurs peut également servir ici de train d’union entre l’élément colon et l’élément indigène…

Over the next few decades, Rouanet’s work with the indigenous musical scene would bring him in two directions. On the one hand, he began to write and talk directly to scholars, including the attendees at the 1905 Congress of Orientalists in Algiers and the readers of leading musicological journals in Paris, bringing him into a more rarefied atmosphere than his usual journalistic interventions.[26] On the other hand, Rouanet began to closely collaborate with indigenous musicians. His collaborations with Yafil resulted in the publication of a series of transcriptions from the urban repertoire, the formation of an Arab music ensemble sometimes known as Orchestre Rouanet et Yafil (which would later morph into the Société El Moutribia), and involvement in the early recording industry in Algeria.[27] These scholarly and applied aspects of his activity were two sides of the same coin: just as his scholarly publications emphasized the danger of disappearance that Arab music faced, his transcription, recording, and performance activities were geared toward the salvage and revival of this allegedly frozen and decadent music through “modern” methods associated with the French civilizing mission.

The Encylopédie essays are the culmination of Rouanet’s writings and lectures on Arab music, even if he subsequently published shorter works.[28] The two essays were generally well received in the European press, and in 1925 they garnered him the Prix Bordin from the Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres (Anonymous 1925).[29] By this time, however, Rouanet’s “applied” activities around Arab music had receded. It is striking, and was striking already at the time, that Rouanet’s recognition in scholarly circles in Europe roughly coincided with the success of Yafil’s Société El Moutribia, as well as with the very public falling out between Rouanet and Yafil that took place in the pages of La Dépêche Algérienne in 1927 (Miliani 2018). While the proximate cause of the rupture was Rouanet’s charge that Yafil had claimed authors’ rights over the traditional repertoire, it is also possible to read this as a violent assertion of settler difference from the urban indigenous milieu and as a break from Rouanet’s connections with more humble indigenous counterparts who were now sharing the limelight. It is also striking that this was the moment when the Jeunes Algériens who Rouanet so despised were beginning to engage in the public musical revival in which Rouanet had originally had such a hand.[30]

In retrospect, the various sides of Rouanet’s public persona raise some broader questions. It is certainly not surprising to find patronizing, Orientalizing tendencies in relatively sympathetic Jonnart-era treatments of “Hispano-Mauresque” culture, as seen in the letter in La Tafna quoted above. But it is another matter to find a sustained interest in Algerian Arab music in a figure who was a relentless defender of the settler cause against indigenous reformers and Paris-based critics. Even if Rouanet occasionally bowed to mild reform in France’s indigenous policy, throughout his career he remained an implacable foe of the enfranchisement of Algerian Muslims. While he was willing to accept the accession of individual “evolved” Muslims into the charmed circle of full citizenship, he held firmly to a notion of two distinct “races” on the same soil, necessarily divided by culture and therefore by political rights. Why, then, would someone so dismissive of indigenous Algerians be so involved with their arts and artists?

Responding to this question requires a consideration of the substance of Rouanet’s musicological writings in dialogue with the substance of his views on “indigenous affairs.” We have already acknowledged the political import of his emphasis on Arab stagnation and the revivifying power of French tools and methods. But a tracing of the grand argument of his essays in the Encyclopédie underlines just how closely tied the image of Arab stagnation and French power were to his particular melding of musical philology and racial theory (see Chami in this issue). Read as one continuous argument, the two essays present a striking narrative of Arab musical origins, early development through borrowing fueled by rapid expansion of the Muslim empire, medieval crystallization in Spain, the musical culture’s “turning in on itself,” slow decay after 1492, and finally rapid deterioration in the face of European dominance—a temporal sequence that he maps onto the Maghribi landscape itself (see for example p. 2819). This deeply Orientalist narrative of arrested development and decay is of course quite convenient for Rouanet, in that in one fell swoop it solves the problem of how to access the musical past: all one must do is engage in an act of “musical archaeology,” since one can find in present-day musical practice the remnants of the medieval past.

As Bouhadiba has pointed out (2019: 67), a major acknowledged influence on Rouanet is Ernest Renan’s writing on “Semitic” mentality. This is particularly evident in Rouanet’s assertion that Arab Muslim music reflects an Arab Muslim mentality rooted in desert life. If this aspect of his argument feels pulled directly from the second half of the nineteenth century, other aspects of it feel more familiar, and even reflect questions in sociomusicological thought that remain quite current. For example, is music immune to outside influence, or is it a site of outside influence (p. 2748)? Rouanet’s uncertainty with regard to the Arab case speaks to a tension running through both essays regarding the endogenous and the exogenous—the endogenous being about the eternal mentality of a people (here equated with Islam), and the exogenous being about give-and-take, change, influence, and even contagion (Pasler 2012-2013: 54). Throughout, Rouanet combines an insistence on a perennial Muslim “mentality” with an insistence on the importance of borrowing—in other words, according to him, music (particularly sacred music) reflects something original and specific while simultaneously reflecting (particularly in profane music) various accretions, influences, and physical movements. But is this borrowing a source of vitality, or is it a threat to musical integrity? Is music that tends to remain “pareil à lui-même” a sign of decay or of strength (Bouhadiba 2019: 68)? This balancing act complicates Rouanet’s confident narrative of stagnation and decadence, even if he ultimately brushes the tensions under the carpet.

Rouanet’s grand musical argument, despite its contradictions, made sense with regard to his broader colonial politics. His vision of French Algeria was as a settler colony that could only survive in the long term through massive French colonization and through maintenance of a docile Muslim population through what he considered good governance, who might undergo a very slow “evolution” under strict French control but without any extension of citizenship rights. This helps to account for Rouanet’s attention to the nûba repertoire, associated as it was with the “vieux turbans” and the bourgeoisie. In addition, this tradition was treated by him, in print and in his other musical activities, as the most assimilable to European classical conventions. But it is also important to consider some of his broader arguments about essence and influence, which go well beyond the nûba repertoire. Rouanet’s argument about profound Greek influence on Arab music was an elaboration of Salvador Daniel’s argument some six decades earlier, wherein “North African music seemed a potential source of knowledge about Greek music: knowledge of the Other was capable of enhancing knowledge of the self” (Pasler 2012-2013: 28). As in Salvador Daniel’s argument, Rouanet’s emphasis on Greek influence opened a deep connection between Arab and European musical traditions. The temporal depth of Greek influence worked well with Rouanet’s narrative: if Greek theory enriched an excessively simple Arab Islamic music at an early date, and if those imprints can still be heard in a wide variety of music in the Maghrib, particularly in the countryside, then digging back beyond the decadence and decay of the intervening centuries might in fact be an act of de-Orientalization and of drawing closer to something compatible with European music. In this sense, the Greek substrate offers a model of positive influence as well as a substantive link between Arab Islamic music and European music, one that parallels the linkage he makes between Kabyle music and Roman music explored in Nacim Khellal’s contribution to this issue. In its gesture to the deep past, this move also provides a future for Rouanet’s colonial vision of association without assimilation.

Even in his settler milieu, Rouanet’s positions regarding the future of Algeria were profoundly conservative. Whether writing about music or politics, his work played on turn-of-the-century colonial themes all the way to the end of his career on the eve of the Second World War. In his last four years, Rouanet fell uncharacteristically silent. Less than a year after his death in Algiers, the foundations of his paternalistic vision of Algeria’s future would be profoundly shaken.

Bibliography

Anonymous. (1887, 8 March). Création d’un Musée commercial à Alger. La Dépêche Algérienne, p. 3.

Anonymous. (1898, 20 November). Le Petit Athénée. Le Radical algérien, p. 2.

Anonymous. (1898a, 25 November). Le Petit Athénée. Le Radical algérien, p. 2.

Anonymous. (1904, 12 May). Au Petit Athénée : La question Rouanet. La Dépêche Algérienne, p. 4.

Anonymous. (1904a, 18 August). La musique arabe. L’Echo du soir, p. 2.

Anonymous. (1905, 22 October). La fermeture de la bourse du travail. Les Nouvelles, p. 2.

Anonymous. (1922, 14 June). Tribunal Correctionnel d’Alger : Le droit de critique et le droit de réponse dans la presse. Le Tell, p. 2.

Anonymous. (1925, 4 May). Echos-A l’Institut de France. La Dépêche Algérienne. May 4, p. 6.

Anonymous. (1926, 25 September). L’étude du piano. La Dépêche Algérienne, p. 6.

d’Artenac, Raoul. (1892). L’Actualité : C. Saint-Saens. La Gazette algérienne. February 17, pp. 1-2.

Bouhadiba, F. (2019). Etique vs émique dans la conceptualisation et la mise en exergue des spécificités des musiques modales : contextualisme désignatif et descriptif dans les textes de la musicologie francophone, propositions conceptuelles et impact musical. Revue des traditions musicales 13, 63-76.

Candide. (1914, 30 July). La Dépêche Algérienne. Le Progrès,

pp. 1-2.

El Magharbi. (1905, 1 March). Diffusion et Fusion. La Tafna, p. 1.

État civil. (1890). Commune d’Alger. Archives nationales d’outre-mer.

Glasser, J. (2016). The Lost Paradise: Andalusi Music in Urban North Africa. University of Chicago Press.

Jean-Darrouy, L. (1926, 26 April). Premier récital de piano de Gaby Bascans. L’Echo d’Alger, p. 3.

Laloy, L. (1922, 1 January). La musique : Reprise des concerts symphoniques, la musique arabe. La Revue de Paris, 401-409.

Miliani, H. (2004). Le cheikh et le phonographe : notes de recherche pour un corpus des phonogrammes et des vidéogrammes des musiques et des chansons algériennes. Turath 8, 43-67.

Miliani, H. (2018). Déplorations, polémiques et stratégies patrimoniales : á propos des musiques citadines en Algérie en régime colonial. Insaniyat 22(79), 31-47.

Pasler, J. (2012-2013). Musical Hybridity in Flux: Representing Race, Colonial Policy, and Modernity in French North Africa, 1860s-1930s. Afrika Zamani 20-21, 21-68.

R.B. (1892, 12 August). Une nomination. L’Indépendant de Mostaganem, p. 2.

Renan, E. (1855). Histoire générale et système comparé des langues sémitiques. Première partie, Histoire générale des langues sémitiques. Imprimerie Impériale.

Rouanet, J. (1897). Pour les tapis algériens." La Vie Algérienne et Tunisienne 8, 227-229.

Rouanet, J. (1905). La Musique Arabe. Bulletin de la Société de géographie d’Alger, 327.

Rouanet, J. (1906). Esquisse pour une histoire de la musique arabe en Algerie-III. Mercure Musical 15-16, 127-150.

Rouanet, J. (1913, 11 August). Les Problèmes Algériens : Documents pour l’Enquête : Le nationalisme musulman, par André Servier (1). La Dépêche algérienne, p. 4.

Rouanet, J. (1922). La musique arabe. In A. Lavignac & L. de la Laurencie (Eds.), Encyclopédie de la musique et dictionnaire du Conservatoire (pp. 2676-2812). Delagrave.

Rouanet, J. (1922a). La musique arabe dans le Maghreb. In A. Lavignac & L. de la Laurencie (Eds.), Encyclopédie de la musique et dictionnaire du Conservatoire (pp. 2813-2939). Delagrave.

Rouanet, J. (1923). Les Visages de la Musique Musulmane. Revue Musicale, 34-58.

Rouanet, J. (1927). La « Suite » dans la Musique Musulmane. Revue Musicale, 279-291.

Vuillermoz, E. (1923, 23 February). L’édition musicale : La Musique Arabe par Jules Rouanet. Le Temps, p. 3.

Jonathan GLASSER[1]

Notes

[1] Virginia University USA.

[2] For example, Bunnan for Tunisia; Yafil, Aboura, Bensmail, and Boudali Safir for Algeria; and Moulay Idriss and Bin Salam for Morocco.

[3] ANOM/GGA/9H/37/18. Direction des Affaires indigènes « Note. Projet d’impression d’une brochure arabe, » undated.

[4] ANOM/GGA/9H/37/18. Letter from Direction des Affaires indigènes to Mohammed ben Rahhal, 18 April 1904.

[5] ANOM/GGA/9H/37/18. Letter from Imprimerie Jourdan, 26 August 1904.

[6] ANOM/GGA/9H/37/18.

[7] ANOM/GGA/9H/37/18.

[8] ANOM/GGA/9H/37/18.

[9] CADN, Archives des Postes, Tanger, Légation et Consulat 517, Serie A. Folder on Ecole franco-arabe Benghabrit, Tanger, 1894-1905. Letter from Cherisey in Tangiers to Governor General in Algiers, 15 March 1905.

[10] ANOM/GGA/9H/37/18. Ghaouti Bouali to the Directeur des affaires indigènes, 23 March 1906.

[11] ANOM/GGA/9H/37/18. Minutes of letter, Government General Service des publications arabes, « Repartition de l’ouvrage sur la musique arabe d’El Ghaouti, mouderres à Sidi Bel Abbès. »

[12] Bibliothèque nationale de France, Letter from Ghaouti Bouali 19 avril 1928 Tlemcen. In Colin, Dossier 8, Langue des chants andalous du Magrib, 218 fol., In Tome IV Hispanique.

[13] I thank Dwight Reynolds for his input regarding my translation of this passage.

[14] University of Virginia, USA

[15] For his place of birth, see Etat Civil, Archives nationales d’outre-mer, Acte de mariage for Jules Rouanet and Georgette Bory, 16 February 1909, Alger, http://anom.archivesnationales.culture.gouv.fr/caomec2/osd.php?territoire=ALGERIE®istre=38236

[16] For his father’s profession, see Etat civil, Archives nationales d’outre-mer, death record for Paul Rouanet, 4 fev. 1890.

[17] See Anonymous 1887; E.V. 1890.

[18] Citing from L’Akhbar, see R.B. 1892.

[19] See for example the cutting attack on Rouanet and La Dépêche Algérienne more generally, originating in La République Sociale, in Candide 1914.

[20] Ibid., as well as d’Artenac 1892 and Anonymous 1922.

[21] Anonymous 1898.

[22] Anonymous 1898a. I thank Ouail Laabassi for bringing this to my attention.

[23] Anonymous 1904 and Anonymous 1905.

[24] Anonymous 1926; Jean-Darrouy 1926.

[25] Anonymous 1904.

[26] See Rouanet 1905; Rouanet 1906; Glasser 2016.

[27] Miliani 2004: 44n5.

[28] Rouanet 1923; Rouanet 1927.

[29] For example, see Laloy 1922; Vuillermoz 1923.

[30] For Rouanet on the Jeunes Algériens, see Rouanet 1913.

Auteurs les plus recherchés

Articles les plus lus

- التراث الثقافي بالجزائر : المنظومة القانونية وآليات الحماية

- التّراث الشّعبي والتّنمية المستدامة. قراءة في الرّقصات الشّعبيّة

- Les Turcs dans la poésie populaire Melhoun en Algérie. Emprunts et représentations

- Eléments d’histoire sociale de la chanson populaire en Algérie. Textes et contextes

- Mot du directeur du CRASC